by Jonathan Head

BBC

Friday 20 January 2017

Many distraught relatives have called for the search to continue

The announcement on 17 January that the search for MH370 was being suspended should have surprised no-one.

At the tripartite meeting last July of the three countries involved in the search, Malaysia, Australia and China, they agreed that it would not be continued beyond the current 120,000sq km area (46,332 sq miles) of the southern Indian Ocean, unless there was credible new information showing a specific location for the crashed airliner.

Nonetheless the families of the victims have condemned this requirement for a “precise location”, calling it “at best an erroneous expectation, and at worst a clever formulation to bury the search”.

- MH370: What we know

- Is it likely MH370 will ever be found?

- The passengers on board MH370

- MH370: The key pieces of debris

- One man’s search for answers

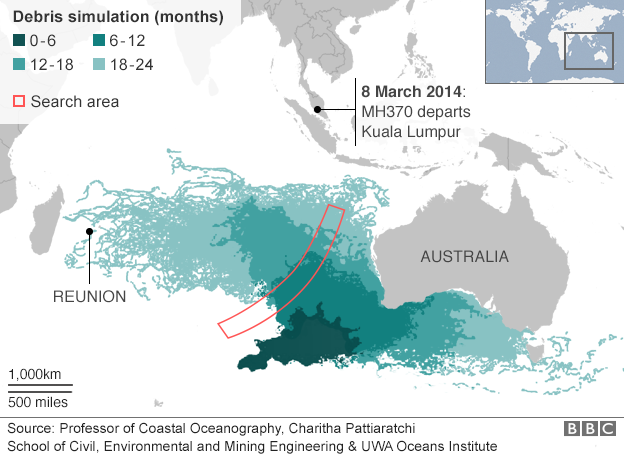

They have pointed to a statement in December by the Australian Transport Safety Board, which is leading the search operation, that in view of the drift modelling carried out by the Australian scientific organisation CSIRO for debris from MH370 found along the East African coast, there was “strong evidence that the aircraft is most likely to be located to the north of the current indicative underwater search area”.

And with no trace of the airliner found after an exhaustive two-and-a-half-year search, all the experts agree they have been looking in the wrong area.

There were 14 nationalities among the 227 passengers and 12 crew on board the plane

The CSIRO drift models suggest the search should be shifted to a 25,000sq km area immediately north of the existing zone, along the arc that satellite data shows the plane must have travelled. It might require an additional $40-50m to extend the search operation into the new area, on top of the $160m already spent.

But the three governments appear unmoved, sticking rigidly to the formula they agreed last July, although the Australian and Malaysian governments insist cost is not a factor in their decision to stop searching.

However in an interview with ABC News on Tuesday, Australian Transport Minister Darren Chester made the point that any decision to resume the search was “primarily Malaysia’s call”.

That underlines a problem which has troubled the search operation from the start: who is really responsible?

Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) staff examine a piece of aircraft debris at their laboratory in Canberra, Australia, July. 20, 2016.

Back in February 2015 Australia submitted a request to the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO), which regulates international air travel, for clearer guidelines on which country should be responsible for both organising and funding an extended search operation.

Under existing guidelines Australia is responsible for initial search-and-rescue efforts in the vast areas of ocean off its western coast. But once it was clear there would be no survivors, it became a search-and-recovery operation, for which responsibility is not clear.

The ICAO designates to Malaysia, the flag state of the missing plane, the task of leading the accident investigation, but it is not clear whether that includes running the extended search.

This was important because by 2015 Australia had shouldered most of the financial burden, and people were beginning to complain. After all, the specialised ships and detection equipment used in the search had to be rented from a Dutch salvage company; any of the three countries could have covered this cost.

Only six of the MH370 passengers were Australians, whereas 153 came from China, which has so far contributed relatively little, around $16m, although the ICAO imposes no requirement on it do so. The Malaysian government now says it has contributed a total of $112m, but the official Australian figures suggest it has actually spent less than that.

So why does Malaysia not take the initiative to fund an extended search? The Malaysian Transport Ministry responded to this question with the formula from last July, that all three countries had agreed they first needed indications of a specific location for the crash site, despite that fact that such detailed information in a huge expanse of sea is extremely unlikely to be found.

Piece of possible MH370 debris found in Madagascar in June 2016

Pieces probably from the plane have been found as far away as Madagascar

Relatives of the passengers have also criticised the Malaysian authorities for being so slow to request recovered pieces of debris, eight of which are now believed to be almost certainly from the missing airliner.

That debris is important: it has not only helped ascertain a probable alternative location for the plane; it has also helped confirm how the aircraft ended its flight, with Australian investigators concluding that it plunged into the sea, and was not under the control of the pilot.

Malaysia has at times given the impression of being a reluctant lead investigator, happy for Australia to do most of the legwork.

Aviation expert Geoffrey Thomas describes Malaysia’s approach as “inexcusable and irresponsible. It is their plane, and their responsibility to find out what happened to it. They are walking away from their commitment to international aviation and the flying public”.

The Malaysian Ministry of Transport says only that “all decisions with regards to the MH370 search have and will always be in the spirit of tripartite co-operation.”

If it is primarily Malaysia’s call to restart the search operation, it looks unlikely to make it.